Two hundred years ago, on the 3rd of June, 1818, my 5 x great grandmother, Gwen, died in a ty-unnos near Strata Florida, Cardiganshire. Her husband, Rees, died a month later. They were in their fifties. One month later, their oldest son Thomas died aged 30 leaving a wife and two small children. This blog post is written on 4th June, 2018, and dedicated to them. They survived extraordinary times only to die under tragic circumstances. Theirs is a poignant tale which amply demonstrates how callous, political decisions can wreak havoc in the lives of ordinary, hardworking people.

Rees was born on a remote farmstead called Hafodeidos and took over this tenant farm from his father, Thomas, when he married Gwen. The last of their children to be born at Hafodeidos was in 1797 because by 1802 they had been dispossessed of this farm and their next and last child was born in a ty-unnos in the first of many of these ‘houses-built-in-a-night’ on nearby common land. Rees was the first to build a ty-unnos on this squatter’s settlement where upwards of twenty such dwellings were eventually built. His son, Hugh, my 4 x grandfather, would also build a ty-unnos here when he married his wife, Mary, in 1811. Hugh and Mary raised nine children here.

According to R.U.Sayce, long moonlit winter’s nights were the favoured times for building ty-unnos. So, on such a winter’s night, Rees and Gwen and their friends would have laid rough stonework foundations and a chimney end, and a framework on this interwoven with stout laths, covered with clay, and smeared with lime-plaster. Timber for the framework came from local woods. Thatch for the roof would have been gathered beforehand. The door and window would have been made in advance, ready to put in place. All materials would have been hidden nearby prior to building. At dawn, the fire was lit and the curl of smoke from the chimney meant the building was complete. The amount of land around the house was determined by the distance the occupant could throw an axe.

The original ty-unnos would have been a flimsy dwelling and was quickly replaced by a more permanent stone-built dwelling over subsequent months. It is the remains of these stone-built dwellings which survive at this squatter’s settlement.

In Radnorshire, they were called ‘Morning Surprise’ – a very apt name as it would have been a great surprise to any passer-by to see a house standing where there was none the day before!

At the time when Rees and Gwen were forced to leave Hafodeidos and live on common land, land agents had begun to take a tougher line with tenants and made in-roads into reducing the length of leases. Custom had long been that leases lasted for 3 generations, i.e. father, son, grandson or father, widow, son. To gain more control over farming practices, agents sought fixed terms. Twenty-one-year leases became more normal but what the landowners and agents were aiming for and eventually succeeded in achieving was for annual renewal.

According to W.J. Lewis, rents per acre rose dramatically in this period during the Napoleonic wars. In Strata Florida, land which had been let for 5 shillings per acre in 1790 had risen to 45 shillings per acre by 1815, while prices fetched for the cattle, horses and pigs the farmers reared fell to between a half and a quarter of the previous years. Great quantities of imported grain and American flour drove prices down further. The years between 1795 and 1802 were also marked by a series of very poor harvests.

Ty-unnos squatters were often referred to by wealthy landowners as ‘the scum of the earth’. Yet, it was these large estate owners who were by far the greatest encroachers and grabbers of the commons, moors and waste lands owned by the Crown, increasing their estates by pushing back the boundary lines and enclosing previously unenclosed lands. But the wealthy were also the lawmakers, able to bring in laws which legitimised the enclosures of common land while outlawing the poor for doing the same. In the words of Alfred Russell Wallace, it was “legalised robbery of the poor for the aggrandisement of the rich who are the lawmakers”.

The disparaging view of the squatters held by the landed gentry is challenged by a study carried out by Jemma Bezant and Kevin Grant. Speaking of the settlement which Rees and Gwen began, they say this squatter settlement went on to prosper into the later 19th century with a total of about 20 dwellings on the site. Originally, they had been one or two-celled, stone-built cottages but by the late 19th century many had acquired brick lined windows, proper chimneys and staircases leading to a second storey. The ‘squatters’ were said to be well-educated, some described as scholars and collectively they had constructed a Calvinist Methodist Chapel to administer to the whole community. The chapel, too, is derelict now, though it shows signs of an abandoned restoration.

And so it was that the poorest in society were demonised and blamed for their predicament, even while it was political decisions which created the circumstances of their poverty and kept them poor, while the wealthiest in society were made ever richer. History repeats itself with alarming banality.

I am immensely proud of these remarkable ancestors who were so resourceful amid times of great hardship. Simon Fairlie, in his Short History of Enclosure in Britain, explains how the poor were able to survive off their rough patch of common land. Here is an extract from his article:

A poor cow providing a gallon of milk per day in season brought in half the equivalent of a labourer’s annual wage and geese at Otmoor could bring in the equivalent of a full time wage. Commoners sheep were smaller, but hardier, easier to lamb and with higher quality wool, just like present day Shetlands, which are described by their breed society as “primitive and unimproved”. An acre of gorse — derided as worthless scrub by advocates of improved pasture — was worth 45s 6d as fuel for bakers or lime kilns at a time when labourers’ wages were a shilling a day. On top of that, the scrub or marsh yielded innumerable other goods, including reed for thatch, rushes for light, firewood, peat, sand, plastering material, herbs, medicines, nuts and berries.

In 1820, William Cobbett wrote the following; “Those who are so eager for the new inclosure, seem to argue as if the wasteland in its present state produced nothing at all. But is this the fact? Can anyone point out a single inch of it which does not produce something and the produce of which is made use of? It goes to the feeding of sheep, of cows of all descriptions . . . and it helps to rear, in health and vigour, numerous families of the children of the labourers, which children, were it not for these wastes, must be crammed into the stinking suburbs of towns?”

Women, too, were able to derive extra income for their families from the commons -from carrying loads of peat from the moors to sell at the coast, to gathering wool shed by sheep on the mountain wastes. I can testify there is certainly no shortage of peat on this common land as I had to walk through half a mile of peat-bog to get to the settlement. It is slowly reclaiming the small parcels of land which were once cultivated here.

Rees and Gwen survived by hard work and making the best they could in times of great adversity. They would have been entirely dependent for food from whatever they could grow and provide for themselves from the small parcel of land they cultivated around their ty-unnos, while making some income from casual summer labour on nearby farms or from the selling of peat and gorse gleaned from the common.

Having survived in this way for over sixteen years, they were to be finally defeated following events which occurred on the other side of the world, in a place they would have known nothing about.

In 1815, there was a massive eruption of Mount Tambora on the island of Sumbawa, Indonesia. The following summer of 1816, there was a ‘volcanic winter’ dubbed ‘the summer that never was’ and it preceded widespread famine across Europe. In Wales, it was said to have caused terrible suffering for hill farmers and dwellers. By 1817, another summer of poor weather, many of the poor were wandering around the Cardiganshire countryside begging food and work at the houses of gentry.

On 7th June that year, a David Williams of Bronmeurig was moved to write of the distress of the hungry poor. Bronmeurig is only a couple of miles north west of the settelement. He stated;

‘ …the imagination cannot conceive the prevalent distress – none but those who witness it can conceive its extent and its intensity…The farmer cannot employ the labourer because he has neither Corn, Money nor Credit to give as recompense for work done….the whole of the labouring population is out of employment and have been these last six months…The poor are attempting to prolong life by swallowing barley meal with water – boiling nettles etc – and scores in the agonies of famine have declared to me this last week that they have not made a meal for two days together….hundreds have therefore been in the constant habit of begging from door to door….I fear half the labouring poor will perish as things are, before next harvest in this neighbourhood…I have witnessed scenes of distress and wailing and lamentation and ungovernable ebullitions of rage prompted by the severest suffering…that my memory will bear the impression wherever I go and as long as I live.’

To add insult to injury, the Black Act of 1723 was still in force. This most vicious Act against the poor was brought in by Walpole. It made the poaching of wild game a hanging offence in Britain and was in response to gangs of poachers who blackened their faces to avoid detection – hence the name. Thus, it became as great a crime to kill a wild rabbit for food as it was to commit murder. To add to the injustice, the landowning gentry were granted license to hunt wild animals for sport, while a hungry man desperate to feed his family could be hung for killing a rabbit, even if it crossed his garden.

Rees and Gwen and their children would have suffered unimaginable hardship and hunger. In the summer of 1818, within weeks of each other, Rees and Gwen Jones and their son, Thomas, died at the squatter’s settlement. Causes of death were not recorded in the parish registers but were most likely to have been the succumbing to disease precipitated by weakness due to the preceding famine.

The little river which runs below the settlement.

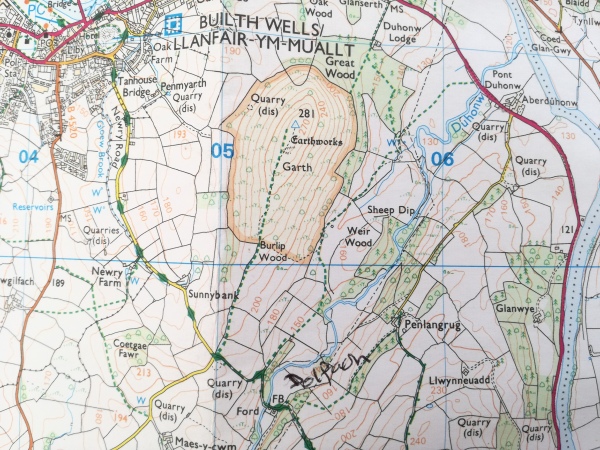

Rees and Gwen’s son Hugh, my 4 x grandfather, and his wife Mary, survived these terrible times and my 3 x grandfather Rees was born at the squatter’s settlement in 1820. Hugh and Mary moved to Brynbedw in the parish of Tirabad in the 1830’s. Hugh was a shepherd and Mary was a healer of some renown. Their son, my 3 x grandfather Rees, worked in Abergwesyn as a shepherd. Here he met and fell in love with Mary Jenkins of Penybont Uchaf. Their children, including my 2 x grandfather, Hugh, were born at Blaengwenol. Their daughter, Mary, was the grandmother of the Anglo-Welsh poet, Harri Jones. I have no doubt that the writing gene has come from this side of my family and is one for which I shall be forever grateful.

In the 1870’s, Rees and Mary moved to Llanerchyrfa along the stunningly beautiful Abergwesyn pass on the mountain road between Abergwesyn and Tregaron. Mary died here, and their two youngest daughters died here, aged just 23 and 28.

Two hundred years on, I wanted to pay my respects and visit the squatter’s settlement where these ancestors lived and died. It was quite an adventure to find this place and very moving to finally stand within the remains of where they lived and died.

Jenny Lloyd is the Welsh author of The Megan Jones trilogy; historical novels set in early 19th century, rural Wales.

You can read about the books or purchase them by clicking on the links below.

Leap the Wild Water: http://ow.ly/jEoi302jXkd

The Calling of the Raven: http://ow.ly/4uRO302jXmd

Anywhere the Wind Blows: http://ow.ly/73tq302Ov71

You can also follow the author:

Facebook; https://www.facebook.com/jennylloydauthor

Pinterest; http://www.pinterest.com/jennyoldhouse